Beyond the Blueprint: 5 Ways Digital Twins are Breathing Life into the Machines of Tomorrow

The Pulse in the Machine

Amid the sterile projections of the global energy transition, wind turbines are often reduced to icons of efficiency. To the senior systems engineer, however, these assets are anything but simple. A modern wind turbine is a cyber-physical organism: a sophisticated nervous system of sensors, a circulatory system of data flow, and a complex hierarchy of interconnected subsystems including blades, gearboxes, towers, and control software. (Chen et al., 2021)

The main obstacle to this organism’s survival is operational friction within the clean energy nexus. The systemic instability of such massive hardware in volatile environments leads to a predictable crisis: unplanned downtime. Traditional conceptual models are often too brittle to bridge the gap between “clean energy” ideals and the volatile reality of the field. (Gijón et al., 2025) Enter the Digital Twin (DT): not a static simulation, but a flexible, bidirectional framework that “lives” alongside the physical asset. It provides the digital pulse necessary to transform a hunk of metal into a self-aware, predictive system.

Takeaway 1: Your Infrastructure Needs a “Live Pulse,” Not Just a Map

The most common mistake in digital transformation is confusing a model for a twin. A static model is a map; a Digital Twin is the real-time pulse of the territory. To use the analogy from current aviation and infrastructure, a static model shows you the road, but a Digital Twin is Google Maps, depicting real-time traffic intensity and evolving conditions as they happen.

This denotes an important shift in industrial paradigms. While legacy SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems provide a “status image” (a mere snapshot of the present), the Digital Twin possesses temporal depth, narrating the past, present, and predicted trajectory of the asset. (Nair et al., 2025) The digital asset becomes a strategic mirror, enabling “decisions within a data model” before a single wrench is applied to the hardware. As the fundamental architecture dictates:

“A digital twin is not a static simulation model; rather, it is a dynamic framework that is fed by sensor and data streams, continuously calibrated, capable of self-correction, and able to establish a bidirectional interaction with the physical system.”

Takeaway 2: The Power of the “Hybrid Brain” (AI + Physics)

There is a persistent myth that pure “black-box” AI can solve any industrial challenge. In high-risk systems such as wind turbines, pure AI often founders on the reality of “imbalanced failure data”: because turbines rarely fail, there is insufficient data to train a purely data-driven model. Conversely, pure physics models regularly break down under the weight of real-world measurement noise and computational complexity.

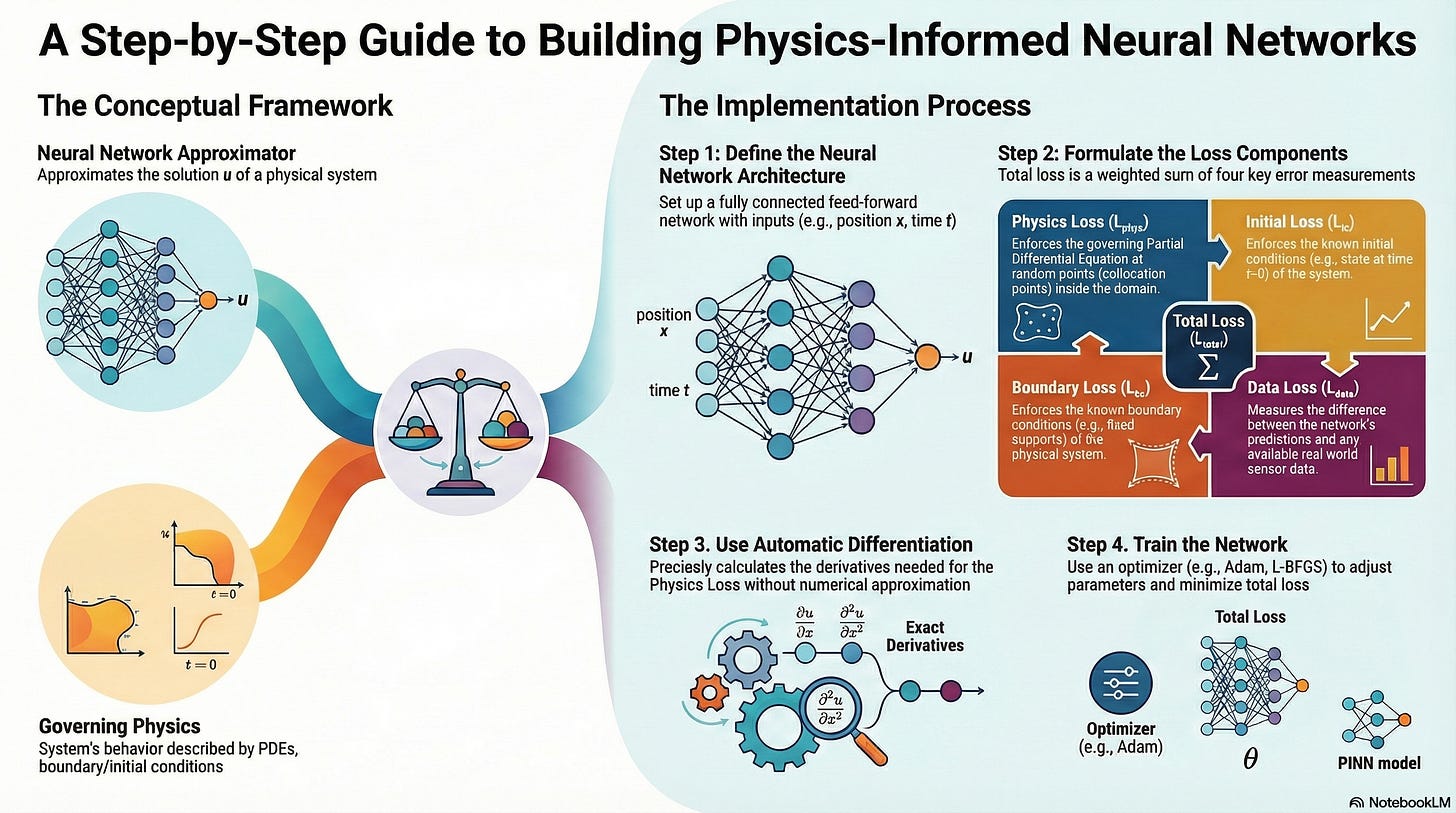

The solution is the “Hybrid Brain,” specifically through Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). By constraining AI learning with established physical laws (such as the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow), we create a system that remains grounded in reality even when data is sparse. (Yan et al., 2024)

A purely physics-based approach fails the Futurist’s test of field-readiness for three reasons:

Overwhelming Computational Cost: High-fidelity modeling of every microscopic variable is too slow for the “real-time” requirements of a digital pulse.

Inherent Measurement Uncertainty: Field sensors are rarely pristine; rigid physical simulations cannot reconcile the “noise” of a storm.

The Rare Failure Paradox: Because disastrous failures are outliers, AI cannot learn to predict them without the guardrails of physical constraints to guide its logic.

Takeaway 3: The “Sufficiently Accurate” Paradox

For the systems engineer, perfection is the enemy of uptime. The “Sufficiently Accurate” Paradox suggests that the most high-precision model is often a strategic liability. There is an inescapable trade-off between model correctness and computational load.

We must view this as a tactical deployment decision: High-fidelity Finite Element Method (FEM) models are the province of “offline” deep-dive analysis, whereas Reduced Order Models (ROMs) or fast-physics twins are the tools of the “real-time” edge. (A.P.-S. et al., 2025) For field operations, a model that is “sufficiently accurate and fast” provides immediate tactical value.

If an operator must adjust pitch control in seconds to prevent a cascading fault, they require the “Live Pulse” of an ROM, not a multi-hour simulation. The architecture of the twin must be dictated by the use case—monitoring versus long-term fatigue analysis—not by an abstract pursuit of precision.

Takeaway 4: From “What Broke?” to “When Will It Break?” (RUL)

The evolution of Digital Twins is shifting Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) away from reactive damage detection toward proactive Prognostics. (Cho et al., 2025) Legacy SHM is binary: a sensor detects a crack on a blade and issues an alert. The Digital Twin transforms this detection into a Stochastic Risk Profile by calculating Remaining Useful Life (RUL).

By relating specific damage to the machine’s unique load history and the specific wind regimes it has survived, the twin moves beyond “what happened” to “when will it matter.” This turns maintenance into a financial lever for revenue protection.

“In the world of wind turbines, data is the ‘blood’ of the digital twin... image-based damage detection can state ‘the damage has been observed,’ whereas a digital twin aims to relate the same damage to load history, wind regime, and operating modes.”

Takeaway 5: Scaling the Twin—From Components to Entire Ecosystems

The future of the Digital Twin lies in transitioning from component-specific monitoring (e.g., a main bearing) to “System-of-Systems” farm-scale logic. At this scale, we have to account for “wake effects”: the turbulent interactions in which the energy harvest of one turbine creates an aerodynamic cover over the next. (Wake impact on aerodynamic characteristics of horizontal axis wind turbine under yawed flow conditions, 2019, pp. 383-392)

Managing this requires a Unified 2D/3D Environment to serve as a Single Source of Truth. BIM (Building Information Modeling) software, such as Revizto or Revit, provides the visual layer needed to unify these disparate data streams. (Revizto Unity platform for BIM collaboration, 2025) At the farm level, the Digital Twin ceases to be a mere maintenance tool; it becomes a decision-support layer for grid integration and regional energy planning. These unified environments allow designers, engineers, and field contractors to coordinate within a single digital reality, ensuring that the “farm-scale twin” remains a coherent ecosystem rather than a collection of isolated parts.

Conclusion: The Future is Autonomous (and Explainable)

We are moving toward the era of the Autonomous Digital Twin: systems that not only predict failures but execute operating parameters to avoid them with minimal human monitoring. However, the final hurdle is not technical, but cultural: the factor of Trust.

Senior systems engineers know that an operator will not decommission a multi-million dollar asset based on a “black box” prediction. We require Explainable AI (XAI) to bridge the gap between machine logic and human insight. Trust is further built through the maturation of global standards such as ISO 23247 and ISO 19650, which ensure our digital pulses use a common, standardized language. (Immersive Digital Twin under ISO 23247 Applied to Flexible Manufacturing Processes, 2026, pp. 1-15)

As our machines begin to speak for themselves and predict their own futures, the question remains: Are we willing to trust the “digital pulse” over our own intuition?

References

Chen, X., Eder, M. A., Shihavuddin, A. & Zheng, D. (2021). A Human-Cyber-Physical System toward Intelligent Wind Turbine Operation and Maintenance. Sustainability 13(2). https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/2/561

Gijón, A., Eiraudo, S., Manjavacas, A., Schiera, D. S., Molina-Solana, M. & Gómez-Romero, J. (2025). Integrating Physics and Data-Driven Approaches: An Explainable and Uncertainty-Aware Hybrid Model for Wind Turbine Power Prediction. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.07344

Nair, R. R., Babu, T., Panthakkan, A., Balusamy, B. & Mansoor, W. (2025). Hybrid Autoencoder-Based Framework for Early Fault Detection in Wind Turbines. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.15010

Yan, C., Xu, S., Sun, Z., Lutz, T., Guo, D. & Yang, G. (2024). A Framework of Data Assimilation for Wind Flow Fields by Physics-informed Neural Networks. Applied Energy 371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123719

A.P.-S., J.G.-E., D.D.C., B.S.-C. & I.B.-P. (2025). Real-Time Digital Twin for Structural Health Monitoring of Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. MDPI 13(10). https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1312/13/10/1953

Cho, H., Yu, J., Moon, H., Yoon, J., Lee, J., Kim, G., Park, J. & Ryu, S. (2025). Real-Time Structural Health Monitoring with Bayesian Neural Networks: Distinguishing Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty for Digital Twin Frameworks. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.03115

(2019). Wake impact on aerodynamic characteristics of horizontal axis wind turbine under yawed flow conditions. Renewable Energy 136, pp. 383-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.12.126

(August 12, 2025). Revizto Unity platform for BIM collaboration. Construction PA News. https://www.constructionpanews.com/revizto-bim-collaboration/

(2026). Immersive Digital Twin under ISO 23247 Applied to Flexible Manufacturing Processes. MDPI, pp. 1-15. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/14/10/4204

Yes, The Future is Autonomous, and I'm doing my best to grasp. This coaching helps